My reference to McConnell’s In Laws as China People resulted in my being called a racist. But those who know me know I am not racist. But they know that I am a concerned American.

As a “business person” I know a conflict of interest when I see one. McConnell and his wife have a major conflict of interest. It is encouraging to see that the NY Times now sees that conflict as well.

Those “big city people” may be slow but they are catching on.

Long read so get yourself a cup of coffee.

A ‘Bridge’ to China, and Her Family’s Business, in the Trump Cabinet

Elaine Chao has boosted the profile of her family’s shipping company, which benefits from industrial policies in China that are roiling the Trump administration.

Source: New York Times

By Michael Forsythe, Eric Lipton, Keith Bradsher and Sui-Lee Wee

June 2, 2019

The email arrived in Washington before dawn. An official at the American Embassy in Beijing was urgently seeking advice from the State Department about an “ethics question.”

“I am writing you because Mission China is in the midst of preparing for a visit from Department of Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao,” the official wrote in October 2017.

A redacted email about a trip Ms. Chao was planning to take to China. A request to include family members at events raised ethical concerns.

In China, the Chaos are no ordinary family. They run an American shipping company with deep ties to the economic and political elite in China, where most of the company’s business is centered. The trip was abruptly canceled by Ms. Chao after the ethics question was referred to officials in the State and Transportation Departments and, separately, after The New York Times and others made inquiries about her itinerary and companions.

“She had these relatives who were fairly wealthy and connected to the shipping industry,” said a State Department official who was involved in deliberations over the visit. “Their business interests were potentially affected by meetings.”

The move to notify Washington was unusual and a sign of how concerned members of the State Department were, said the official, who was not authorized to speak on behalf of the agency.

[The Chao family has deep ties to the world’s two largest economies. Here are five takeaways.]

David H. Rank, another State Department official, learned of the matter after he stepped down as deputy chief of mission in Beijing earlier in 2017. “This was alarmingly inappropriate,” he said of the requests.

The Transportation Department did not provide a reason for the trip’s cancellation, though a spokesman later cited a cabinet meeting President Trump had called at the time. The spokesman said that there was no link between Ms. Chao’s actions as secretary and her family’s business interests in China.

Ms. Chao has no formal affiliation or stake in her family’s shipping business, Foremost Group. But she and her husband, Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, have received millions of dollars in gifts from her father, James, who ran the company until last year. And Mr. McConnell’s re-election campaigns have received more than $1 million in contributions from Ms. Chao’s extended family, including from her father and her sister Angela, now Foremost’s chief executive, who were both subjects of the State Department’s ethics question.

Over the years, Ms. Chao has repeatedly used her connections and celebrity status in China to boost the profile of the company, which benefits handsomely from the expansive industrial policies in Beijing that are at the heart of diplomatic tensions with the United States, according to interviews, industry filings and government documents from both countries.

Now, Ms. Chao is the top Trump official overseeing the American shipping industry, which is in steep decline and overshadowed by its Chinese competitors.

Her efforts on behalf of the family business — appearing at promotional events, joining her father in interviews with Chinese-language media — have come as Foremost has interacted with the Chinese state to a remarkable degree for an American company.

Foremost has received hundreds of millions of dollars in loan commitments from a bank run by the Chinese government, whose policies have been labeled by the Trump administration as threats to American security. The company’s primary business — delivering China’s iron ore and coal — is intertwined with industries caught up in a trade war with the United States. That dispute stems in part from the White House’s complaints that China is flooding the world with subsidized steel, undermining American producers.

Foremost, though a relatively small company in its sector, is responsible for a large portion of orders at one of China’s biggest state-funded shipyards, and has secured long-term charters with a Chinese state-owned steel maker as well as global commodity companies that guarantee it steady revenues.

In a rarity for foreigners, Angela and James Chao have served on the board of the holding company for China State Shipbuilding, a state-owned enterprise that makes ships for the Chinese military, along with Foremost and other customers. Angela Chao is also on the board at the Bank of China, a top lender to the shipbuilder, and a former vice chairman of the Council of China’s Foreign Trade, a promotional group created by the Chinese government.

Angela Chao, speaking in an interview in New York on Friday, said that her board positions were unremarkable, emphasizing that Foremost did business around the world. She denied that the company had a “China focus” beyond what most dry bulk carriers have in a world dominated by Chinese manufacturing. “We are an international shipping company, and I’m an American,” she said, adding, “I don’t think that, if I didn’t have a Chinese face, there would be any of this focus on China.”

James Chao was not made available for an interview; a representative of the company received written questions from The Times two weeks ago, and the company responded with a fact sheet on Friday.

Though Foremost worked in the late 1960s on American government contracts to ship rice to Vietnam, according to James Chao’s biography, it has almost no footprint left in the United States, save for a modest corporate headquarters in Midtown Manhattan. It registers its ships in Liberia and Hong Kong and owns them through companies in the Marshall Islands.

Since Elaine Chao became transportation secretary, records show, the agency budget has repeatedly called to cut programs intended to stabilize the financially troubled maritime industry in the United States, moving to cut new funding for federal grants to small commercial shipyards and federal loan guarantees to domestic shipbuilders.

Her agency’s budget has also tried to slash spending for a grant program that helps keep 60 American-flagged ships in service, and has tried to scale back plans to buy new ships that would train Americans as crew members. (In China, Ms. Chao’s family has paid for scholarships and a ship simulator to train Chinese seamen.)

Congress, in bipartisan votes, has rejected the budget cuts, some of which have been offered up again for next year. One opponent of the cuts has been Representative Alan Lowenthal, a California Democrat whose district includes one of the nation’s largest cargo ports.

“The Chinese government is massively engaged in maritime expansion as we have walked away from it,” he said in an interview. “There is going to come a crisis, and we are going to call upon the U.S. maritime industry, and it is not going to be around.”

Elaine Chao declined to be interviewed, but the Transportation agency provided a written statement from her.

“My parents and I came to America armed only with deep faith in the basic kindness and goodness of this country and the opportunities it offers,” Ms. Chao said. “My family are patriotic Americans who have led purpose-driven lives and contributed much to this country. They embody the American dream, and my parents inspired all their daughters to give back to this country we love.”

The department spokesman said The Times’s reporting wove “together a web of innuendos and baseless inferences” in linking Ms. Chao’s work at Transportation to her family’s business operations.

Agency officials said the department under Ms. Chao had been a champion of the American maritime industry, adding that several proposed cuts had been made by previous administrations and that the Trump administration had since moved to bolster funding.

Ms. Chao, 66, was born in Taiwan to parents who had fled mainland China in the late 1940s and later settled in the United States when she was a schoolgirl. She worked at Foremost in the 1970s but has had no formal role there in decades.

As her political stature has grown — she has served in the cabinet twice and has been married to Mr. McConnell for 26 years — Beijing has sought to flatter her family. A government-owned publisher recently printed authorized biographies of her parents, releasing them at ceremonies attended by high-ranking members of the Communist Party. On a visit last year to Beijing, Ms. Chao was presented with hand-drawn portraits of her parents from her counterpart in the transportation ministry.

The Chao family’s ties to China have drawn some attention over the years. In 2001, The New Republic examined them in the context of the Republican Party’s softening tone toward the country. When Ms. Chao was nominated as transportation secretary, ProPublica and others highlighted the intersection of her new responsibilities with her family’s business. And in a book published last year, the conservative author Peter Schweizer suggested the Chaos gave Beijing undue influence.

The Times found that the Chaos had an extraordinary proximity to power in China for an American family, marked not only by board memberships in state companies, but also by multiple meetings with the country’s former top leader, including one at his villa. That makes the Chaos stand out on both sides of the Pacific, with sterling political connections going to the pinnacle of power in the world’s two biggest economies.

Ms. Chao’s father, a founder of Foremost in 1964, has for decades cultivated a close relationship with Jiang Zemin, a schoolmate from Shanghai who rose to become China’s president. As the schoolmates crossed paths again in the 1980s, the Chaos reaped dividends from a radar company linked to Mr. Jiang that targeted sales to the Chinese military, documents filed with the Chinese government show.

Though Ms. Chao’s financial disclosure statements indicate she receives no income from Foremost, she made at least four trips to China with the company in the eight years between her job as labor secretary during the George W. Bush administration and her confirmation as transportation secretary in January 2017. And her father accompanied her on at least one trip that she took as labor secretary, in 2008, sitting in on meetings, including with China’s premier, one of the country’s top officials.

Public records show that she has benefited from the company’s success. A gift to Ms. Chao and Mr. McConnell from her father in 2008 helped make Mr. McConnell, the Republican majority leader, one of the richest members of the Senate. And three decades worth of political donations have made the extended family a top contributor to the Republican Party of Kentucky, a wellspring of Mr. McConnell’s power.

“This is a family with financial ties to a government that is a strategic rival,” said Kathleen Clark, an anti-corruption expert at Washington University in St. Louis. “It raises a question about whether those familial and financial ties affect Chao when she exercises judgment or gives advice on foreign and national security policy matters that involve China.”

A Family Business on the Rise

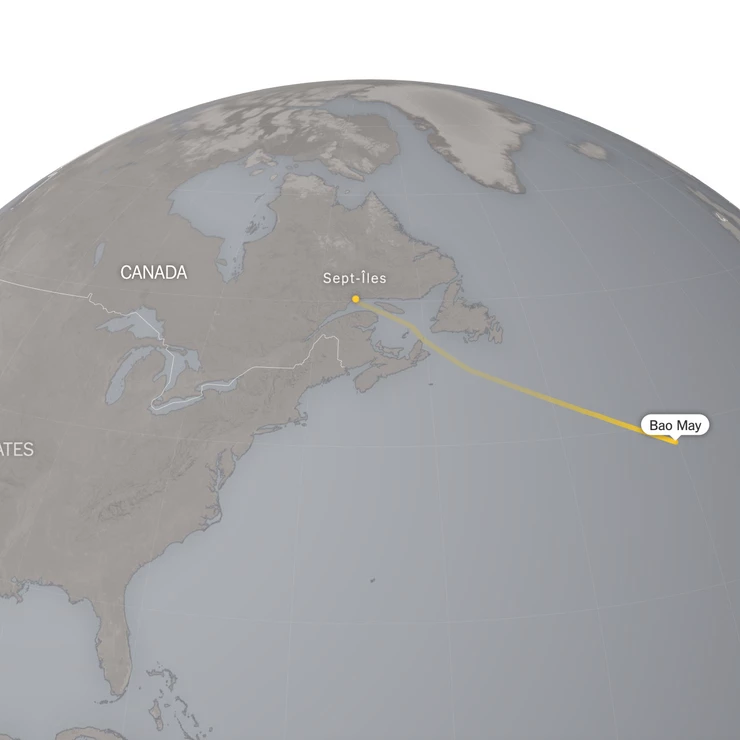

Elaine Chao, the transportation secretary, has been a steadfast booster of her family’s shipping business, which transports raw materials to fuel China’s heavy industries. In January 2017, as the Senate voted to confirm Ms. Chao, a bulk carrier ship sailed from Canada with a shipment of iron ore.

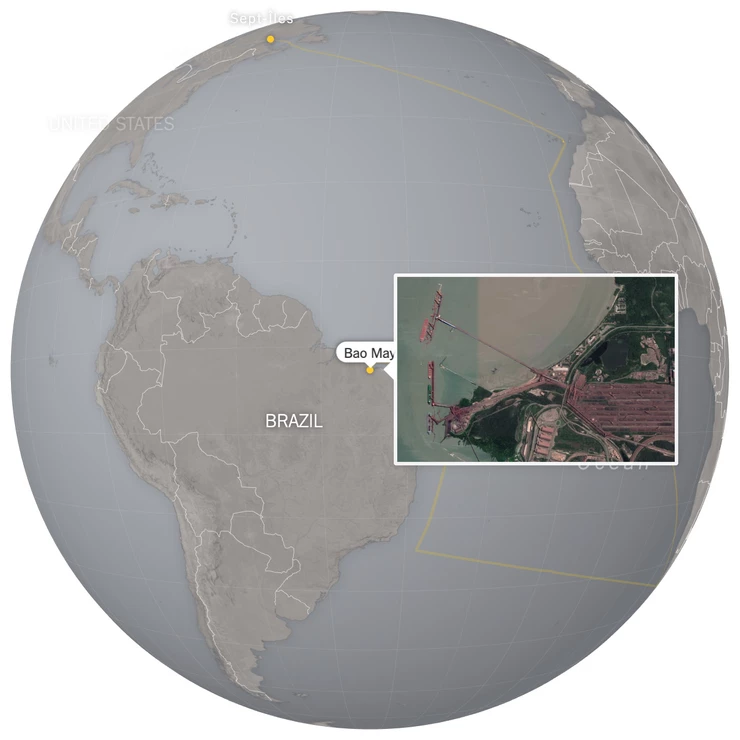

The ship, the Bao May, is owned by her family’s business, Foremost Group. Its destination: an iron ore transfer terminal on Liangtan Island, south of Shanghai.

Two weeks later, after unloading its cargo in China, the Bao May set sail for Brazil to collect another shipment of iron ore, weaving through the Strait of Malacca and crossing the Indian Ocean.

The size of three football fields, the Bao May is too big to pass through the Suez or Panama Canals, so it must sail around the southern tip of Africa on its voyages to Atlantic Ocean destinations. For the last two years, the Bao May has repeatedly made the round-tip journey between China and ports in Brazil and Canada.

On this trip, it arrived in Brazil in May 2017, docking at the Ponta da Madeira Maritime Terminal in São Luís, where ships load up with iron ore from Brazil’s interior.

The Bao May was built in a Chinese shipyard and financed with loans from the Export-Import Bank of China, owned by the Chinese government. At the launch ceremony in Shanghai in 2010, the guest of honor was Ms. Chao. For years, the ship has been chartered by a state-owned Chinese steelmaker, giving Foremost a steady supply of revenue.

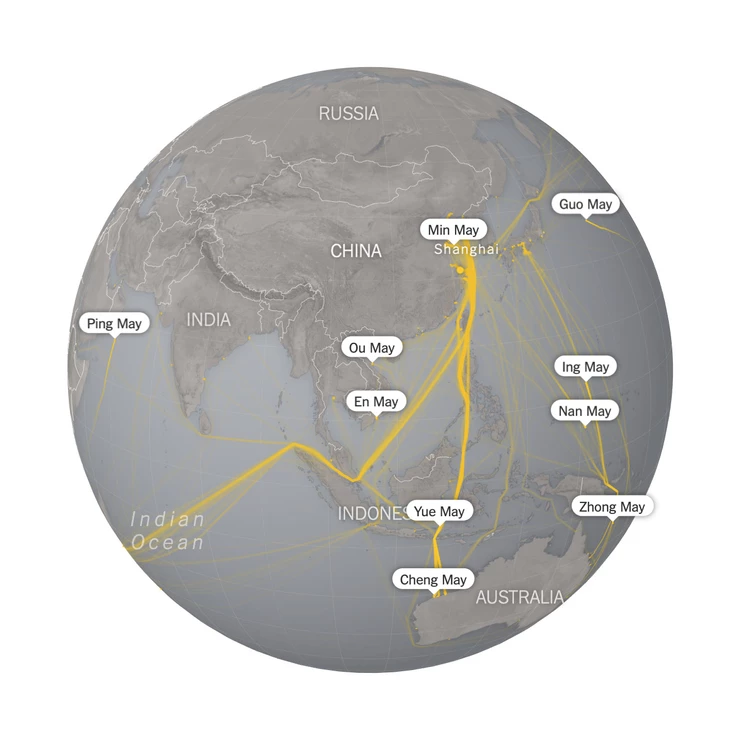

It is one of 19 ships owned by Foremost, which was founded by Ms. Chao’s father, James S.C. Chao, and is now run by her sister Angela.

Data source: VesselsValue

While Foremost has its headquarters in Midtown Manhattan, its fleet is overwhelmingly focused on China. About 72 percent of the raw materials it has shipped since the beginning of 2018 has gone to China, according to figures from VesselsValue, a London-based firm that analyzes global shipping data.

Each year, Foremost ships transport hundreds of millions of tons of iron ore, coal and bauxite to China from ports around the globe. The shipments feed China’s industrial engine, especially its steel mills, whose products are part of an escalating trade dispute between China and the United States.

Rich Harris/The New York Times. Source: VesselsValue. Bao May image: Tropic maritime images. Satellite imagery: Google Earth

Four enormous gantry cranes rise on the banks of the Yangtze River near the East China Sea. In their shadow thousands of workers assemble cargo ships, each about as long as three football fields.

It is here, at the Shanghai Waigaoqiao shipyard, that Foremost Group’s newest ship, the Xin May, was built. Six similar ships are set to be built in the next several years, all part of an order by Foremost announced in December 2017 at the Harvard Club in New York.

Foremost first placed an order with the state-owned company in 1988 and over the decades has been its biggest North American customer, according to the shipbuilder. The relationship is so tight that Foremost’s offices in Shanghai are in the shipbuilder’s 25-story tower.

“We are committed to continuing to build ships in China,” Angela Chao said at the Harvard Club announcement, which was attended by the top official in China’s New York consulate. “My father was a pioneer in internationalizing the Chinese shipbuilding market, and it has been over 30 years that he has continuously ordered ships in China.”

The newest addition to the Foremost fleet, the Xin May, is one of multiple ships the company has ordered from the Shanghai Waigaoqiao shipyard.

Foremost has relied on the Export-Import Bank of China, or China EximBank, to finance at least four ships in the past decade. Its loans often come with lower interest rates and more generous repayment schedules than those made through some commercial lenders. As of 2015, the bank had made at least $300 million available to Foremost, it said at the time.

Angela Chao, in the interview with The Times, said that 2015 was the last year the company borrowed from the lender, describing its terms as less attractive than those of non-Chinese banks. She said the company never borrowed — “not even close” — $300 million, a figure she had not previously heard. “They are not a big part of our financing,” she said.

The Chao family’s connections run deep with the Chinese leadership, documents in China show.

As civil war raged across the country in the 1940s, Mr. Chao attended Jiao Tong University in Shanghai. A schoolmate was Mr. Jiang, who stayed in China after the Communist victory and ultimately became president. Mr. Chao went with the defeated Nationalists to Taiwan, where he became the youngest person to qualify as a ship’s captain, according to his biography.

Mr. Chao left for the United States in 1958, but a thaw in relations sparked by President Richard M. Nixon drew him back to his homeland in 1972, the first of a flurry of trips that established him as a successful member of the Chinese diaspora.

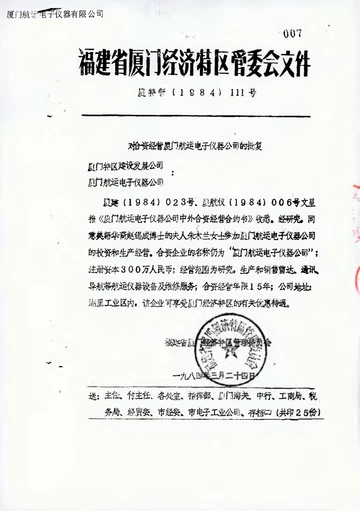

Mr. Chao got exceptional access. In 1984 he was invited to Beijing to celebrate the 35th anniversary of the People’s Republic and meet with the country’s top leader, Deng Xiaoping, according to materials at a museum in Shanghai dedicated to Mr. Chao’s wife, Ruth Mulan Chu Chao, who died in 2007.

Also in 1984, as China emerged from decades of political and economic turmoil, Ruth Chao bought a stake in a Chinese company that manufactured marine equipment, including radars, in partnership with Raytheon, the American defense contractor, according to Chinese corporate documents.

The investment, not previously reported, was held by a Panamanian company. The Chinese company, documents show, praised the “support for the construction of the nation” shown by Ruth Chao, identifying her as James’s wife and both of them as American citizens.

The now-defunct company targeted the Chinese military for sales of some of its gear, and a principal partner was a state-owned factory under the Ministry of Electronics Industry, which was led at the time by Mr. Jiang, according to corporate documents and a former employee. The employee, Zheng Chaoman, recalled the involvement of “the father of Elaine Chao.”

Within months, it generated enough revenue for Mr. Chao to donate profits to a foundation he had established in Shanghai, according to an announcement by the local government. The foundation sponsors training scholarships for merchant seamen, his wife’s biography said.

In the aftermath of the deadly suppression of pro-democracy demonstrations on Tiananmen Square in June 1989, the Chaos asked to divest their 25 percent stake in the company. Two months earlier, Elaine Chao had been confirmed by the Senate to a senior political appointment, as deputy transportation secretary under President George H. W. Bush.

The Transportation Department spokesman said Ms. Chao did not know anything about the venture. Angela Chao, in the interview, said her father did not “remember any ownership, and we can’t find anything on it.”

The family’s other business ties in China remained, including work that year by China State Shipbuilding on two new cargo ships for Foremost.

That August, Mr. Chao met with Mr. Jiang, who had been named general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, the country’s most powerful position. Their hourlong meeting inside the leadership compound adjacent to the Forbidden City, together with the head of the state shipbuilding company, was described as “friendly” in the official People’s Daily newspaper.

The two former schoolmates would meet at least five more times during Mr. Jiang’s tenure as general secretary, according to a review of publicly available documents.

A Celebrity Face for the Company

As the first Chinese-American to serve as a cabinet secretary — eight years as labor secretary — Elaine Chao became an instant celebrity in China during the George W. Bush administration. Her family was a beneficiary of her newfound fame.

During a trip to China in August 2008 to represent the United States at the closing of the Olympic Games, Ms. Chao took her father to several official meetings with Chinese leaders, including one with the country’s premier, Wen Jiabao, according to diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks. At the time, Mr. Chao was chairman of Foremost and a board member of China State Shipbuilding.

When she left government during the Obama years, she continued to put her celebrity status to use on behalf of the family business.

In 2010, she traveled to Shanghai with her father for the delivery ceremony of a cargo ship, the Bao May. The ship soon became a workhorse for Foremost, hauling raw materials to China from around the world under a seven-year charter with a subsidiary of a state-owned steel maker. Foremost paid for the Bao May and another ship with up to $89.6 million in loans from China EximBank, corporate records in Hong Kong show.

The next year, Ms. Chao was back in Shanghai for the launch of another ship, and in 2013, she traveled to Beijing with her father and her sister Angela for a meeting with the chairman of China State Shipbuilding, according to a company announcement.

Ms. Chao joined her family two years later at the signing of a loan for Foremost at China EximBank’s grand hall in Beijing. The loan, for $75 million, was made jointly with a Taiwanese lender to build two cargo ships.

The Transportation Department spokesman said it was “entirely appropriate” for Ms. Chao to take her father to meetings in 2008 as her “plus-one,” and said her visits between her government posts were done as a private citizen.

Angela Chao said her sister attended Foremost events “as a family member.”

“Foremost was founded in 1964; the company is 55 years old,” she added. “We were around and we were well respected well before Elaine was in anything. We predate her; she doesn’t predate us.”

The flurry of visits coincided with Foremost’s growing contributions to China’s globalized steel and shipping industries.

Today, Foremost’s fleet, like many, primarily serves the Chinese market, hauling bulk cargo such as iron ore, coal and bauxite. Of the 152 voyages made by its ships between Jan. 1, 2018, and April 12, 2019, 91 have been to or from China, accounting for 72 percent of Foremost’s total tonnage during that period, according to figures compiled by VesselsValue, a company that tracks shipping data.

Angela Chao said that its ships were chartered to commodity companies such as Cargill, and that Foremost did not “control where the ships go, so we’re like a taxicab.”

During her eight years out of government, Elaine Chao extended her connections in China, according to a review of Chinese websites and other public materials.

For example, she was appointed in 2009 to an advisory group in Wuhan, where the steel maker with the Foremost charter is based. Such appointments are largely ceremonial, but they can be sought after for the access they sometimes provide to local leaders.

That same year, she was granted an honorary professorship at Fudan University, and in 2010, she was awarded an honorary doctorate from Jiao Tong University.

With Mr. Trump’s election, Ms. Chao was asked to join the administration. During her confirmation hearing she did not discuss her family’s extensive ties to the Chinese maritime industry, and she did not disclose the various Chinese accolades she had received. The Senate’s written questionnaire requires nominees to list all honorary positions.

“It was an oversight,” the Transportation Department spokesman said.

A Budget at Odds With Congress

Ms. Chao has spoken repeatedly about her commitment to the American maritime industry, including during her confirmation hearing in 2017.

“I’m of an age where I have seen two wars in pivotal areas of the world,” she told the Senate Commerce Committee, with her father seated behind her. “If we did not have the merchant marine assets to assist the gray hulls on these campaigns, the military naval campaigns, our country would not have been able to supply our troops, bring the necessary equipment.”

But without Congress putting up roadblocks, some of the Trump administration’s budgetary actions proposed during her tenure would have reduced federal funding for programs that support the shipbuilding industry and ships that operate under American flags.

Plans drafted during the Obama administration had called for building up to five new, state-of-the-art ships big enough to train 600 cadets each to help the American military move equipment and supplies worldwide, especially during wartime.

But after Ms. Chao became secretary, the agency’s budget proposed buying old cargo ships instead and renovating them. Congress balked at the cost-cutting measure — one Democratic lawmaker mocked the agency’s plan to “buy a bunch of rusty old hulks” — and restored the funding.

More recently, the agency budget pushed to shrink the size of one of the new ships, again provoking bipartisan protests from Congress.

“Given the administration’s strong commitment to American manufacturing and to being sure that we can adequately control the seas, the targeting of programs that help the maritime industry remain strong doesn’t make sense to me,” said Senator Susan Collins of Maine, the Republican who leads the panel overseeing the Transportation Department budget. “It seems inconsistent with the administration’s overall goals.”

Ms. Collins added that the driving force behind these cuts had been the White House, not Ms. Chao, whom the senator called a “strong advocate” for the maritime program.

The agency budget in 2017 and 2018 also proposed reducing annual grants for the Maritime Security Program, which help American ships pay crews and cover the cost of meeting safety and training requirements.

It also moved in the last three years to eliminate new funding for a grant program that helps small shipyards stay in business, as well as a program that provides loan guarantees for the construction or reconstruction of American-flagged vessels.

Agency officials noted that many of the cuts were forced on the department by the White House, and that some of the same programs had been previously targeted, only to see the money restored by Congress, as happened with the Trump cuts.

Ms. Chao has supporters in the industry, citing her work to defend a federal program that allows only American-flagged ships to make deliveries between American ports, as well as the effort to replace training vessels, which has boosted the maritime unit’s overall budget.

“We have a secretary who comes from the maritime industry — and that has translated into an understanding of the importance of the maritime academies,” said Jerry Achenbach, superintendent of the Great Lakes Maritime Academy in Michigan.

But objections continue, including questions about why, despite repeated promises, Ms. Chao has not issued a detailed strategic plan for stabilizing the United States’ shrinking fleet.

Fair Kim, a retired Coast Guard deputy commander who works at an association that promotes the American shipping industry, said Ms. Chao and the Trump administration had a disappointing maritime record.

“If you preach America first, why not promote the U.S.-flagged fleet at the expense of foreign-flagged ships?” he asked. “This administration should be very friendly to us.”

A China-Friendly Approach

The Trump administration has made the rivalry with China a core tenet of American foreign policy, concluding that decades of accommodation has reinforced the country’s authoritarian rule and undermined the interests of the United States.

“Beijing is employing a whole-of-government approach, using political, economic and military tools, as well as propaganda, to advance its influence and benefit its interests in the United States,” Vice President Mike Pence said during a speech in October.

None of that, however, has kept Ms. Chao from maintaining China-friendly relations, including engaging with the Chinese media about her family’s shipping business and multiple other subjects. During a televised interview, one prominent Chinese reporter, Tian Wei, described Ms. Chao as “a bridge” between Beijing and the Trump administration.

Ms. Chao’s official calendar, obtained by The Times through a public records request, shows at least 21 interviews or meetings with Chinese-language news organizations in her first year as transportation secretary.

In November 2017, she met for lunch at her office with Ma Jing, then the top official in the United States for CGTN, the China state television network.

The network has been under growing pressure from the Justice Department to detail its ties to the Chinese state as part of a stepped-up enforcement of foreign influence laws, and in March, Ms. Ma and a dozen other CGTN employees in Washington were reported to have been recalled to China.

In an interview in April 2017, Ms. Chao was photographed with her father next to a Transportation Department flag. Her father told the reporter how he had traveled on Air Force One and discussed “business” with the president.

He also took the opportunity to talk up his daughter’s new role in the administration. “It’s not just an honor for us Chinese,” Mr. Chao said to The China Press, a publication in the United States. “It’s an honor for Americans.”

The interview was first highlighted by Politico, which noted that Ms. Chao had made multiple media appearances with her father.

Ms. Chao’s schedule also shows that she attended an August 2017 event in New York celebrating the signing of a Foremost deal with Sumitomo Group, a Japanese company with mass transit projects in the United States, including California and Illinois, that fall under her oversight. The spokesman said she attended in a personal capacity and did not discuss agency business.

Marilyn L. Glynn, a former general counsel at the Office of Government Ethics, questioned Ms. Chao’s proximity to Foremost, saying she should recuse herself from decisions that broadly impacted the shipping industry.

“She might be tempted to make sure her family company is not adversely affected in any policy choices, or it might even just appear that way,” Ms. Glynn said.

The agency spokesman said that was not necessary because there was no conflict. “The family business is not in U.S.-flag shipping,” he said. “The trade routes are completely different; the ships are completely different.”

The original trip had been described by the department as a “bilateral meeting” with Ms. Chao’s Chinese counterpart to discuss disaster response, infrastructure and related subjects.

Eight days before the planned start of the October 2017 trip, when contacted by The Times, Ms. Chao’s office said it could not provide a list of who would accompany her.

But the embassy in Beijing had received requests to accommodate Ms. Chao’s family members, according to interviews with State Department officials involved in the planning, as well as a redacted email obtained by The Times through a public records lawsuit.

Angela Chao said in the interview that she was already planning to be in Beijing to attend a Bank of China board meeting, and that her husband, the investor Jim Breyer, also had business in the Chinese capital. But she said she was unaware of her sister’s travel plans. Angela Chao was among the family members mentioned in the State Department discussions about the visit, according to a United States official.

The email, with the subject “ethics question,” had come from Evan T. Felsing, a senior economic officer for the State Department in Shanghai. Mr. Felsing, now based in India, declined to comment.

Other correspondence also signaled unease among American diplomats over whom Elaine Chao intended to take on the trip and the topics they would discuss with Chinese officials. Emails indicate that ethics lawyers in both the State and Transportation Departments weighed in.

“They would not have raised a question like this about a cabinet secretary unless it was something really serious,” said Mr. Rank, the former deputy chief of mission in Beijing, who resigned in protest over the Trump administration’s environmental policy.

The agency spokesman confirmed a request on behalf of Ms. Chao’s relatives, but did not say in his written response to questions whether they were scheduled to attend official government events.

When Ms. Chao finally traveled to China last April, no relatives were present.

She met with top leaders, including the premier, Li Keqiang. While there, she sought to soothe hard feelings between China and the Trump administration in an interview with a government-run broadcaster. She suggested some of the tensions resulted from cultural differences.

“America is a very young country — it’s very dynamic — it doesn’t have a long period of history,” she said in an interview with CGTN. “So there are not so many rules and regulations in terms of behavior, whereas some other countries that have long histories, it may be a little bit more different. We have to understand the Chinese and how they see things, and I think the Chinese need to understand how America sees things.”

Even this trip did not proceed entirely by the book. Ms. Chao broke with the standard practice for government employees and flew on a Chinese state airline instead of an American carrier.

Ms. Chao’s economy-class round-trip ticket with Air China cost $6,784, according to information obtained through a public records request. The flight was booked through a code-share arrangement with United Airlines. A less expensive ticket was available on a nonstop United flight, according to an airline official.

The agency spokesman would not say what class Ms. Chao flew in, only that the ticket was booked in economy. The flight, he said, complied with federal law.

A Windfall for Mitch McConnell

When a delegation of local Chinese Communist Party leaders visited Washington in 2017, Ms. Chao’s office arranged for them to be photographed with Ms. Chao and her father.

Her aides pulled another string.

“U.S. Capitol Tour for VIP Guests,” read the subject line of an email sent by Ms. Chao’s aides to the staff of her husband, Mr. McConnell.

The senator’s staff obliged, arranging an “off limits” tour for Ms. Chao’s guests, who were visiting from the home region of her mother.

“The delegation was thrilled to get the VIP treatment by your office and were particularly excited to hear that the leader’s office was normally off limits to normal guests,” an aide to Ms. Chao later wrote to Mr. McConnell’s staff.

It was a small favor, but one that reflected the political partnership at the center of the marriage between Ms. Chao and Mr. McConnell.

In 1989, shortly after their first date (at the Saudi ambassador’s home near Washington), Mr. McConnell was preparing for a re-election campaign. Greetings from Ms. Chao came in classic Washington fashion: a string of campaign donations, totaling $10,000, from Ms. Chao, her father, her mother, her sister May and May’s husband, Jeffrey Hwang, according to Federal Election Commission records.

Over the next 30 years, the extended Chao family would be an important source of political cash for Mr. McConnell, himself one of the most formidable Republican fund-raisers in American politics.

The extended Chao family is among the top donors to the Republican Party of Kentucky, giving a combined $525,000 over two decades.

One of Ms. Chao’s sisters, Christine, the general counsel at Foremost, was the second-biggest contributor to the super PAC Kentuckians for Strong Leadership in 2014. She gave $400,000 to the organization, which identified Mr. McConnell’s re-election as its highest priority that year.

In all, from 1989 through 2018, 13 members of the extended Chao family gave a combined $1.66 million to Republican candidates and committees, including $1.1 million to Mr. McConnell and political action committees tied to him, according to F.E.C. records.

“I’m proud to have had the support of my family over the years,” Mr. McConnell said in a statement.

The family’s wealth has also benefited Mr. McConnell personally. In 2008, Ms. Chao’s father gave the couple a gift valued between $5 million and $25 million, according to federal disclosures. Mr. McConnell, never a wealthy man, vaulted up the moneyed rankings in the Senate; as of 2018 he was the 10th wealthiest senator, according to Roll Call, the Capitol Hill newspaper. David Popp, a spokesman for Mr. McConnell, said the gift from Mr. Chao was in honor of Elaine Chao’s mother.

Over the years, Mr. McConnell has also participated in Chao family events and trips related to the family’s business and charitable giving.

In 1993, he and Ms. Chao traveled with her father to Beijing at the invitation of China State Shipbuilding and met top officials.

He celebrated Foremost’s 50th anniversary in 2014 at the Harvard Club in Manhattan, witnessing the signing of a contract with a Japanese shipbuilder.

And he attended the dedication in 2016 of a building at the Harvard Business School named after Ms. Chao’s mother. Ms. Chao and three of her sisters had attended the school.

Mr. McConnell’s connection to the family was hard to miss when a reporter recently visited the Foremost headquarters in Manhattan. There, in the reception area, were two gray pillows emblazoned with the seal of the United States Senate.

Ailin Tang contributed reporting from Shanghai. Susan C. Beachy, Jack Begg and Elsie Chen contributed research.

A version of this article appears in print on June 2, 2019 of the New York edition with the headline: A Cabinet Official, a Firm And a ‘Bridge’ to Beijing.